Palace of Knossos Europe's oldest city !

- Jan 10, 2019

- 8 min read

Arena scene fresco, Knossos, Crete, 1600 BCE. Minoans crowded into the seats to watch bull leaping

As soon as you enter the palace through its West court, it is clear how the legends of the labyrinth grew up around it. Even with a map and description, it can be very hard to work out where you are.

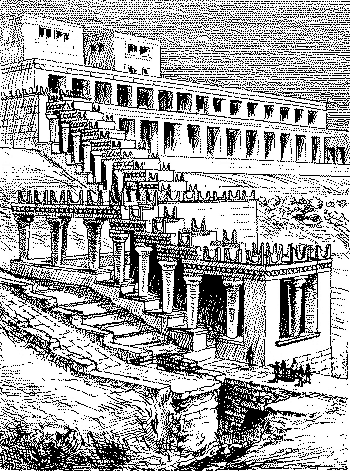

The remains you see are mostly those of the second palace, rebuilt after the destruction of around 1700BC and occupied-with increasing Myceneaen influence- through to about 1450BC. At the time, it was surrounded by a town of considerable size. The palace itself, though must have looked almost as much of a mess then as it does now- a vast bulk, with more than a thousand rooms on five floors, which had spread across the hill more as an organic growth than a planned building, incorporating or burying earlier structures as it went. In this, Knossos simply followed the pattern of Minoan architecture generally with extra rooms being added as the need arose. It is a style of building still common on Crete, where finished buildings seem to be outnumbered by those waiting to have an extra floor or room added when need and finance dictate.

The difficulty in understanding the site is not helped by the fact that you are no longer allowed to wander freely through the complex: instead, a series of timber walkways channels visitors around. This is particularly true of the Royal Apartments, where access to many rooms is denied or reduced to partial views from behind glass screens. The walkways also make it almost impossible to avoid the guided tours that congregate at every point of significance en route.

The Legend of the Minotaur

Knossos was the court of the legendary King Minos, whose wife Pasiphae, cursed by Poseidon, bore the Minotaur, a creature half-bull, and half man. The Labyrinth was constructed by Daedalus to contain the monster, and every nine years seven youths and seven maidens were brought from Athens as human sacrifice, until finally Theseus arrived to slay the beast and with Ariadne’s help, escape its lair. Imprisoned in his own maze, Daedalus later constructed the wings that bore him away to safety- and his son Icarus to his untimely death.

The West Court

The west court, across which you approach the palace, was perhaps a marketplace or, at any rate, the scene of public meetings. Across it run slightly raised walkways, leasing from the palace’s West Entrance to the Theatric Area, and once presumably on to the Royal Road. There are also three large circular pits, originally grain silos or perhaps depositories for sacred offerings, but used as rubbish tips by the end of the Minoan era.

When these were excavated, remains of early dwellings-visible in the central pit, dating from around 2000BC and thus preceding the first palace-were revealed. The walls and floor surfaces were found to have been coated with red plaster, and these are among the earliest-known remains on the site.

Following the walkway towards the West Entrance nowadays, you arrive at a stones marking the original wall of an earlier incarnation of the palace, then the façade of the palace proper, and beyond that a series of small rooms of which only the foundations survive.

The first Frescoes

Anyone entering the palace by the West Entrance in its heyday would have passed through a guardroom and then followed the Corridor of the Procession, flanked by frescoes depicting a procession, around towards the south side of the palace; the walkway runs alongside. A brief detour down the stairway near the West Entrance would enable you to view the South House before entering the palace proper.

The Sough house, reconstructed to its original three floors, seems amazingly modern, but actually dates from the late Minoan period (c.1550 BC) the dwelling is believed to have belonged to an important official or noble, since it encroaches on the palace domain. It’s also a cult room with a sacred pillar and stands for double axes and a libation table.

Following the walkway you come to the reproduction of the Priest-King fresco, Prince of the Lilies. The nearby viewing point offers a chance to look down over the palace. Apparently, a whole series of large and airy frescoed chambers, perhaps reception rooms, once stood there.

The Central Court

The heart of the palace is aligned almost exactly north-south. The courtyard paving covers the oldest remains found on the site, dating back to Neolithic times. In Minoan times high walls would have hemmed the courtyard in on every side, and the atmosphere would have been very different from the open, shade less space which survives. Some say this was the scene of the famous bull-leaping, but that seems unlikely: although the court measures almost 50m by 25m, it would hardly be spacious enough to accommodate the sort of intricate acrobatics shown in surviving pictures, let alone an audience to watch.

The Throne Room

The entrance to one of Knossos most atmospheric survivals is in the northwestern corner of the central courtyard. Here, a worn stone throne sits against the wall of a surprisingly small chamber; along the walls around it are ranged stone benches and, behind, there’s a copy of a fresco depicting two griffins. In all probability, this was the seat of a priestess rather than a ruler-there’s nothing like it in any other Minoan palace-but it may just have been an innovation wrought by the Mycenaean, since it appears that this room dates only from the final period of the palace’s occupation. Opposite the throne, steps lead down to a lustrum basin-a sunken “bath”, probably for ritual purification rather than actual bathing, with no drain.

The Piano Nobile

Alongside the Throne Room, as stairway climbs to the first floor and Evans’s reconstructed Piano Nobile. One of the most interesting features of this part of the palace is the view it offers of the palace storerooms, with their rows of pithoi (storage jars). There’s an amazing amount of storage space here, in the jars-which would mostly have held oil or wine-and in sections sunk into the ground for other goods. The rooms of the Piano Nobile itself are again rather confusing, though you should be able to pick out the Sanctuary Hall from stumps that remain of its six large columns. Opposite this is a small concrete room (complete with roof), which Evans “reconstructed” directly above the Throne Room. It feels entirely out of place; inside, there’s a small display on the restoration of the frescoes, and through the other side you get another good view over the Central Court. Returning through this room, you could climb down the very narrow staircase on your right to arrive at the entrance to the corridor of storerooms (fenced off) or head back to the left toward the area where you entered the palace.

The Royal Apartments

On the east side of the central courtyard, the Grand Staircase leads into the Royal Apartments, clearly the finest of the rooms at Knossos, though sadly you can’t enter any of them. The staircase itself is a masterpiece, not only a fitting approach the these sumptuously appointed chambers, but also an integral part of the whole design, its large well allowing light into the lower storey. Light wells such as these, usually with a courtyard at the bottom, are a common feature of Knossos and a reminder of just how important creature comforts were to the Minoans, and how skilled they were at providing them.

For more evidence of this luxurious lifestyle, you need look no further than the Queen’s Suite, off the grand Hall of the Colonnades at the bottom of the staircase. The main living room is decorated with the celebrated dolphin fresco and with running friezes of flowers and (earlier) spirals. On two sides it opens to courtyards that let in light and air; the smaller one would probably have been planted with flowers. It is easy to imagine the room in use, scattered with cushions and hung with rich drapes, curtains placed between the pillars providing privacy and cool shade in the heat of the day. Guides will describe all this but it is of course almost entirely speculation-and some of it pure con. The dolphin fresco, for example, was found in the courtyard, not the room itself, and would have been viewed from inside or above as a sort of trompe l’oeil, like looking out of a glass-bottomed boat. There are many who argue, convincingly, that grand as these rooms are, they not really large or fine enough to have been royal quarters. Those would more likely have been in the lighter and airier rooms that must have existed in the upper reaches of the palace, while these lower apartments where inhabited by resident nobles or priests.

The Queen’s Bathroom, its clay tub protected behind a low wall (and probably screened by curtains when in use), is another fine example, as is the famous ‘flushing” lavatory (a hole in the ground with drains to take the waste away-it was flushed by a bucket of water).On the floor above the queen’s domain, the Grand Staircase passes through a set of rooms which are generally described as the King’s Quarters. These are chambers in a considerably sterner vein. The staircase opens into a grandiose reception area known as the ruler’s personal chamber, the Hall of the Double Axes- a room which could be divided to allow for privacy while audiences were held in the more public section or the whole opened out for larger functions. Its name comes from the double-axe symbol, so common throughout Knossos, which here is carved into every block of masonry.

The drainage system

From the back of the queen’s chambers, you can emerge into the fringes of the palace where it spreads down the lower slopes of the hill. This is a good point at which to consider the famous drainage system at Knossos, some of the most complete sections of which are visible under grilles. The snugly interconnecting terracotta pipes ran underneath most of the palace (here, they have come more or less direct from the Queen’s Bathroom), and site guides never fail to point them out as evidence of the advanced state of Minoan civilization. Down by the external walls you get a clear view of the system of baffles and overflows designed to slow down the runoff and avoid flooding.

The Palace Workshops

From the bottom of the slope, you get a fine impression of the scale of the whole palace complex and can circle around towards the north, climbing back inside the palace limits to see the area known as the Palace workshops. Here potters, lapidaries and smiths appear to have plied their trades, and this area is also home to the spectacular giant pithoi. There is also a good view of the Bull Relief fresco set up by the north entrance.

Around the North Entrance

Circling around the palace, you can re-enter by the North Entrance. Beside the gateway is a well-preserved lustrum basin, and beyond that, a guardroom. As you head up towards the central courtyard, a flight of stairs doubles back to allow you to examine the copy of the Bull Relief close up. Just outside the North Entrance, the Theatric Area is one of the most important enigmas of this and other Minoan palaces. An open space resembling a stepped amphitheatre, it may have been used for ritual performances or dances, but there’s no real evidence of this, and again there would have been very little room for an audience if that was its function.

Beyond it, the Royal Road sets out: originally this ran to the Little Palace and probably on across the island beyond that, but nowadays it ends after about 100m at a brick wall beneath the modern road. Alongside are assorted structures variously interpreted as stores, workshops or grandstands for viewing parades, all of them covered in undergrowth.

Comments